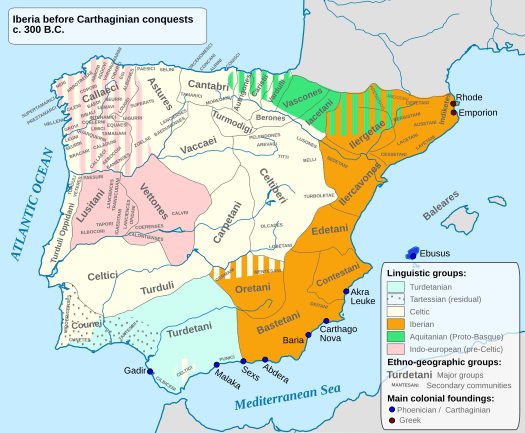

The name Valencia comes from the Romans, who named it Valentia Edetanorum, from the Latin Valentia, ‘valor’ and Edetanorum, the Edetanis being the Iberian people who populated the area. Roman soldiers arrived in 138 BCE, with Valencia’s founding credited to cónsul romano Décimo Junio Bruto.

The soldiers chose to build on what is commonly termed an island. A small branch of the Turia River circled a zone of slightly elevated terrain. You can still see the path today although the stream is underground. It moves approximately along Guillem de Castro, Xativa/Colon then to Porta del Mar (Port of the Sea).

The location is a high spot on the Turia River several kilometers inland, today the area surrounding the Real Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados (The Royal Basilica of Our Lady of the Forsaken) generally referred to as the Almoina. Refer to the drawing below. There was a wooden bridge crossing the Turia, probably located where the current Torres de Serrano is located, called “Pont de Fusta,” as it is written in Valenciano, meaning “Wooden Bridge.” Straight across the rise is approximately where the current Estación de Norte is located. In the center you see the temple and the Forum, where the Real Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados, Cathedral de Valencia and the La Almoina Archaeological Museum are now located. The forum, with government buildings, a temple, baths and the like, was destroyed during the civil war of 75 BCE. The forum was rebuilt as the city recovered.

The forum, with government buildings, a temple, baths and the like, was destroyed during the civil war of 75 BCE. The forum was rebuilt as the city recovered.

The hippodrome, a racetrack that used to be called a “circus”, dates to the 2nd century CE. Vestiges of both it and the forum can be seen today. La Almoina Archaeological Museum is several meters below the current level. The ruins displayed were discovered in the course of work to expand the Basilica in the early 1980’s when Valencia was competing with Barcelona in its worship of the Virgin de los Desamparados.

The remnants of the ninfeo (structures featuring water and plants), the thermal baths, the macellum (grain warehouse), the temple, the forum and many other important buildings of that time lie underground in the area surrounding the Basilica.

Remnants of the hippodrome are now visible in the basement of the Centro de Arte Hortensia Herrero (CAHH), about 5 meters below the current ground level.

During works on the Cathedral Museum workers came across remains of roman houses and streets one meter below ground. They are located beneath the San Francisco and San José chapels. Archaeologists dated the discoveries to the first and second centuries. “Some vital parts of the original structure are preserved, such as lintels, entrances and water vessels, according to the diocesan seminar Paraula, which informs about the unexpected discovery. “https://www.uv.es/uvweb/master-cultural-heritage-identification-analysis-management/en/master-s-degree-cultural-heritage-identification-analysis-management/roman-ruins-cathedral-valencia-1285932165134/GasetaRecerca.html?id=1285966840465

Valencia remained a Roman province until the 6th century, the later stages under Church rule. Then it became part of the Visigoths centered in Toledo.